The origins of human mental health and illness lie in our early life when the brain is undergoing the programs and patterns of organization in structure and function that underlie these differing developmental outcomes. Magnetic resonance imaging, better known as MRI, has become the dominant brain imaging technology used in exploring the complex relationship between the brain and behavior. The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Psychiatric Research Institute’s (PRI) Brain Imaging Research Center (BIRC) has a new state-of-the-art MRI system ideally suited for adolescent and adult brain imaging.

However, the large, tube-like MRI scanner can be overly confining and sensitive to head motion that limit its use in child brain imaging studies, in spite of the fact that it is period of human brain development that holds the greatest potential for research seeking to promote mental and behavioral health and prevent illness.. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy, or fNIRS, a new optical functional brain imaging technique has been added to the BIRC technology suite to overcome the “developmental blind spot” posed by MRI-based child brain imaging research so as to allow a view of the brain without the need for a large, immobile scanner.

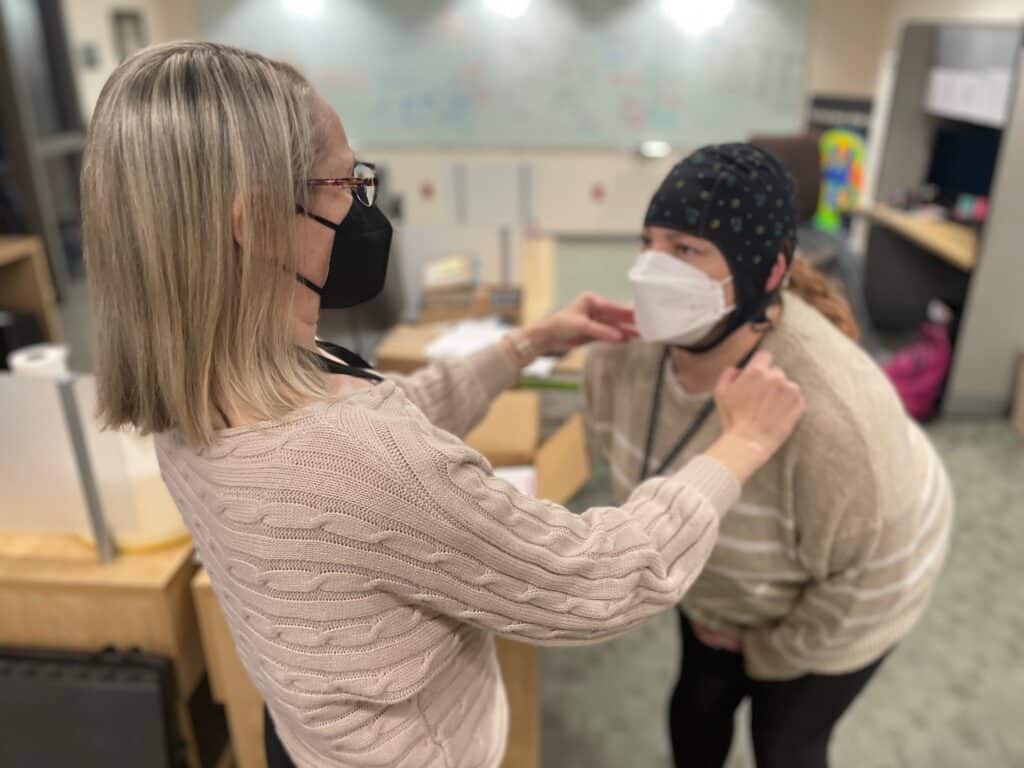

Unlike an MRI scanner, which uses magnets and radio waves to produce images, fNIRS maps brain activity by measuring changes in the properties of light as it shines through the skull and is refracted back to a specialized detector. And, unlike MRI, which requires subjects to lie completely still, the fNIRS system allows participants to behave and interact in an easy manner.

“Kids have a hard time staying still [in an MRI scanner] long enough to give us really good data,” says Maegan Calvert, Ph.D., a child behavioral neuroscientist and child clinical psychologist who joined PRI’s faculty last October. “With [fNIRS], kids wear it like a swimming cap. They can walk around, interact with other, like their parents or siblings. And we can get images of brain responses while they are doing these activities.”

To fund the new PRI Child Brain Imaging Program (CBIP), the BIRC purchased the fNIRS equipment thanks to a grant from the Arkansas Research Alliance and a generous gift from the late Helen L. Porter. In anticipation of using the equipment for upcoming studies, the BIRC has been renovating its space to include what Calvert calls “a very nice playroom” that includes a two-way mirror that will allow researchers to observe the behavior of research participants without any kind of obstruction.

The new equipment and space will allow Calvert and other BIRC researchers to undertake a long-term initiative to gather images of brain activity of children as young as new-born infants; however, Calvert states the BIRC will start their investigations with children 3 to 5 years of age. “Our overall goal is to improve child mental health, particularly children who have experienced adversity like abuse, neglect, poverty and parental incarceration” says Calvert, who believes these new insights can lead to improving mental health treatments and preventive interventions for at-risk children.

Calvert plans to use the CBIP to study not only children playing games and performing learning, memory, behavior control tasks but also their parents. These unique capabilities allow the BIRC to explore the brain developmental correlates of arguably the greatest determinant of child mental health – parenting behavior. “We have two systems, one for a child and one for an adult, which gives us the capability to image two interacting brains at the same time,” she says. “We’ll be able to collect data from the parent while they interact with their child and thereby characterize the brain representations of dynamic parenting behavior.”

Because the equipment is compact and easy to transport, Calvert plans to use it in varying locations outside of the BIRC. “We’re going to be able to go to areas where imaging studies have never gone before, working with rural kids in particular,” she says. “This will give us a better idea of what young brains look like and what they are capable of.”